Focus on the automotive industry – James Bond’s Aston Martin is not “old-fashioned”

In an increasingly design conscious world it’s becoming more important for companies to protect the way their products look. Although design law is the obvious starting point trade mark law can sometimes help. Design registrations are generally relatively easy to obtain and last up to 25 years. By contrast, trade mark registrations can last forever. However, the requirements of trade mark law can be stringent and difficult to meet, as Aston Martin recently found out.

To be registrable a sign must be capable of performing the essential function of a trade mark, namely identifying the origin of the goods or services in respect of which registration is sought, to enable customers coming across the same sign to repeat positive experiences and avoid negative experiences.

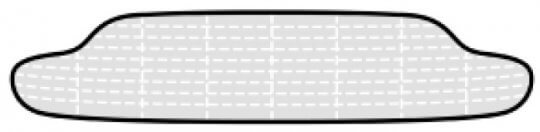

Back in 2013 Aston Martin filed an EUTM application for a figurative mark showing its typical car grille:

The application covered a range of goods, including automobiles and related parts and fittings. Despite admitting that car grilles are no longer purely functional but have become an essential part of the look of vehicles and a means of differentiating between manufacturers, the EUIPO concluded that the grille here departed little from what might come to mind if someone were asked to draw a typical car grille from memory. The application was rejected.

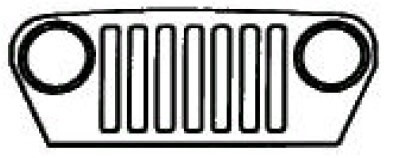

This contrasts with an earlier decision by the General Court relating to a Jeep car grille:

It was found that the Jeep car grille displayed features of undeniable inherent distinctiveness. The design conveyed the impression of an “old-fashioned grille” and therefore was considered to be “unusual” and not “commonplace” at the time protection was sought.

Despite two trips to the Board of Appeal, Aston Martin’s attempts to show their grille had acquired distinctiveness through use failed. Sales figures, marketing activities and massive media exposure, including in several James Bond films, were not sufficient to show that consumers throughout the EU saw the grille as a trade mark. The protagonist of the films was James Bond, not his Aston Martin. Even if the viewing public paid particular attention to the Aston Martin, they were unlikely to be mentally registering and recording the shape of the grille. Aston Martin eventually withdrew the application, rather than appealing further. Although only speculation it is possible they liked the idea that James Bond’s cars are not “old-fashioned”.

This case is a reminder of just how difficult it can be to obtain registration for non-traditional trademarks. Where a mark is the product (or part of the product) in relation to which registration is sought, it must depart significantly from the norm to be deemed inherently distinctive. As a result, evidence of acquired distinctiveness will almost always be needed. However, the threshold is high. It must be clearly demonstrated that consumers see the mark as a trade mark – i.e. it is something they rely on when making purchasing decisions. This must be the case both:

- For the relevant average consumer, not just a sub-group – here the goods were automobiles so the test had to be satisfied as regards an average member of the general public, not a car enthusiast or trader; and

- Throughout the EU – in this case evidence was lacking for a number of Member States.

And what about designs? Unfortunately for Aston Martin, due to their own long-standing use of the grille it would no longer meet the novelty requirements for a valid design registration.